Introduction

“Ethical Leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement and decision-making”… [and] the evidence suggests that ethical leader behavior can have important positive effects on both individual and organizational effectiveness” (Rubin, et al., 2010, pp. 216-217)

Background

Ethical leaders encourage their followers to model their behaviours by communicating their standards and use rewards as well as discipline to promote suitable and unsuitable behaviours. Brown et al. (2005), who first quoted the above definition for ethical leadership, had implied implicitly that, the leader’s intent is never to harm his or her followers and act in the best interest of others. The normatively appropriate conduct depends on the context, though certain factors such as honesty, trustworthiness, and fairness are universally appropriate. The normative behaviour could be dependent on the culture, for example, as speaking out against superior’s actions is appropriate in some cultures whereas it is not appropriate in other cultures. Ethical leaders promote ethics by drawing attention to the ethics and make them important by talking to their followers about ethics. They also reinforce these ethics by setting the ethical standards, rewarding those who follow those standards and disciplining those who do not (Treviño, et al., 2003).

Theoretical Framework

According to the Aryee et al. (2002), based on the social exchange theory, the followers of ethical leaders feel that they are in a social exchange with their leaders due to the ethical treatment they receive and the trust they feel, due which their performance improves. According to social learning theory by Bandura (1979), ethical leaders can influence their followers to improve their self-efficacy as they prove to be attractive and legitimate role models, thereby allowing the followers to reach their full potential. There are two sides to the ethics discussion, which are Deontological (Rules) and Teleological (Consequentialist) views. According to the deontological view, the intention is important rather than the outcome. A leader acting according to his or her duty or moral principles is acting ethically, regardless of outcomes or consequences. However, the teleological perspective is dependent on the outcomes and not the actions. Therefore, a leader whose actions bring about the greatest good or something morally good, is acting ethically. Offshoring of jobs could cause distress to some people but by increasing the profits of the company, it achieves a greater good and hence is ethical (Aronson, 2001).

There are two types of deontological views, rule deontology and act deontology. According to rule deontology, a person’s behaviour is ethical only if the person follows a predetermined standards or rules. Therefore, the behaviour is not ethical or unethical based on the consequences but on the rules or standards themselves, which might be composed of a series of guidelines that specify the manner in which an individual must behave to be considered ethical (Vitell & Ho, 1997). According to the act deontology, people act based on a set of norms but there could be exceptions. Individuals are obliged to behave towards others as everybody has rights and dignity, without considering the consequences. Therefore, the concern is about the moral values of the action itself (Aronson, 2001).

There are many types of teleological theories, but the major ones are ethical egoism, act utilitarianism, and rule utilitarianism. In the case of ethical egoism, a person considers an act as moral or immoral based on the likelihood of the act allowing one’s personal objectives and any other outcomes are irrelevant. Act utilitarianism categorises a behaviour based on its potential to provide the greatest good to the greatest number of people, based entirely on the principle of utility. Rules may serve as a guide but they do not form a part of the ethical decision. Rule utilitarianism prescribes that one should conform to a set of rules that provide the greatest good to the greatest number of people (Aronson, 2001).

While traditional literature considers Deontological and Teleological views as opposing each other, Brady (1985) states that Deontologists look back at the culture and tradition for establishing ethical guidelines while Teleologists look forward to finding the solutions that lead to the most positive outcomes of all. Therefore, it is important to use both views simultaneously to resolve ethical issues. However, there is an increase in the use of teleological viewpoint by many organisations or governments when dealing with issues and the deontological viewpoint is becoming secondary (Aronson, 2001).

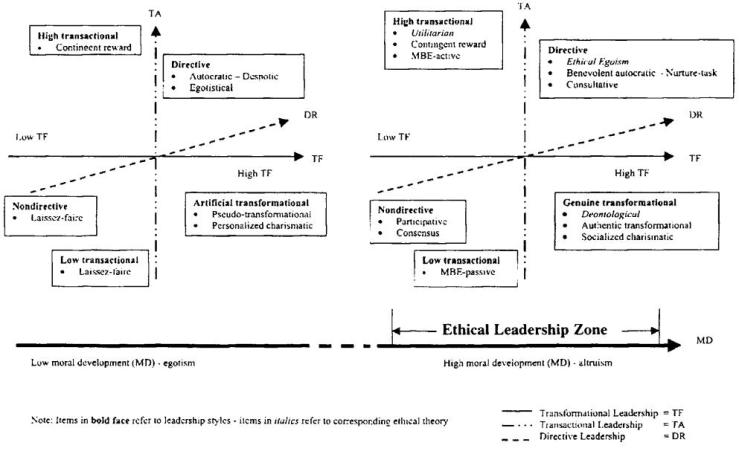

Figure 1: A Model of Ethical Leadership

Source: (Aronson, 2001, p. 250)

Figure 1 shows a model of ethical leadership that tries to reconcile between the various leadership styles and the ethical leadership theories. Experts generally consider transactional and directive leadership as generally low on morals while transformational leadership is generally highly ethical form of leadership as it is associated with high moral development (Aronson, 2001).

Real-Life Examples

Alan S. Weil’s law firm was in the World Trade Centre on September 11 and affected by the event. Immediately after the event, he checked to see that all employees were safe. He immediately rented a building and equipment so that the company was open for business the next day. This had resulted in the greatest good for various stakeholders though he might have acted he was greedy and did not want to lose a day of billings. His personal reasons may not be likeable but his actions created the greatest good for the greatest number of people so according to the teleological view, it was ethical. Similarly, businesses spend on corporate social responsibility activities and other promotional activities. These are with the intentions of promoting the company or for meeting the regulatory requirements. However, they result in greater good and hence they are ethical. Businesspersons who follow all laws may be immoral as laws are moral minimums. Many of the scandals that have been unearthed are a testament to the fact that businesspersons have become unethical in pursuit of outcomes (Ciulla, 2012).

Recommendation for Managers

Good leaders should be both ethical and effective, but there are few leaders who are both. The criteria that are used to judge a leader is also not morally neutral with some of the unethical but effective leaders being lionised. A leader must have concern for others or altruism, ethical decision-making, integrity, and be a role-model, which are part of authentic leadership and transformational leadership models. They should, however, avoid being pseudo-transformational leaders. They should be honest and fair in all their dealings, they should have a history of being ethical, avoid being coercive and manipulative, and must not be selfish and politically motivated. However, they should deviate from transformational leadership and be transactional when setting the ethical standards and holding followers accountable to those standards. They should be ethical role models for their followers, promote ethical culture as a subculture of the organisation, and be morally aware when approaching any issue.

References

Aronson, E., 2001. Integrating Leadership Styles and Ethical Perspectives. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(4), pp. 244-256.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S. & Chen, Z. X., 2002. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of organizational Behavior, 23(3), pp. 267-285.

Bandura, A., 1979. Self-referent mechanisms in social learning theory. American Psychologist, 34(5), pp. 439-441.

Brady, N. F., 1985. A Janus-headed model of ethical theory: Looking two ways at business/society issues. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), pp. 568-576.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K. & Harrison, D. A., 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), pp. 117-134.

Ciulla, J. B., 2012. Ethics and leadership effectiveness. In: D. V. David & J. Antonakis, eds. The nature of leadership. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 508-542.

Rubin, R. S., Dierdorff, E. C. & Brown, M. E., 2010. Do ethical leaders get ahead? Exploring ethical leadership and promotability. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(2), pp. 215-236.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M. & Hartman, L. P., 2003. A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), pp. 5-37.

Vitell, S. J. & Ho, F. N., 1997. Ethical decision making in marketing: A synthesis and evaluation of scales measuring the various components of decision making in ethical situations. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(7), pp. 699-717.

Two deontological views are clearly explained by academic resources at the beginning of the blog. Moreover, you gave real life example which is a very useful perspective as well. You really put a lot of effort on this essay!

LikeLiked by 2 people

An interesting blog and i ant to ask why leaders need to care about it is the right action or the right results?

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment, in my opinion leaders have own special characterizes that’s why they need to care all about these.

LikeLike

A very informative blog, I just want to complete that ethical manager are those who are willing to take a greater approach towards responsibilities.

LikeLike

Which ethical leadership style would you follow in the future and why?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I would choose my own way or according to my job I have to by myself

LikeLike

A valuable though and good example to support ethical leadership.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a good blog! I really liked it!

Now I understand the distinct

difference of the two ethical theories.

LikeLiked by 1 person